British composer Laura Rossi talks about her work for the ballet ‘Atonement’ in Zurich

30. April 2024 by volker-hagedorn.de/wp

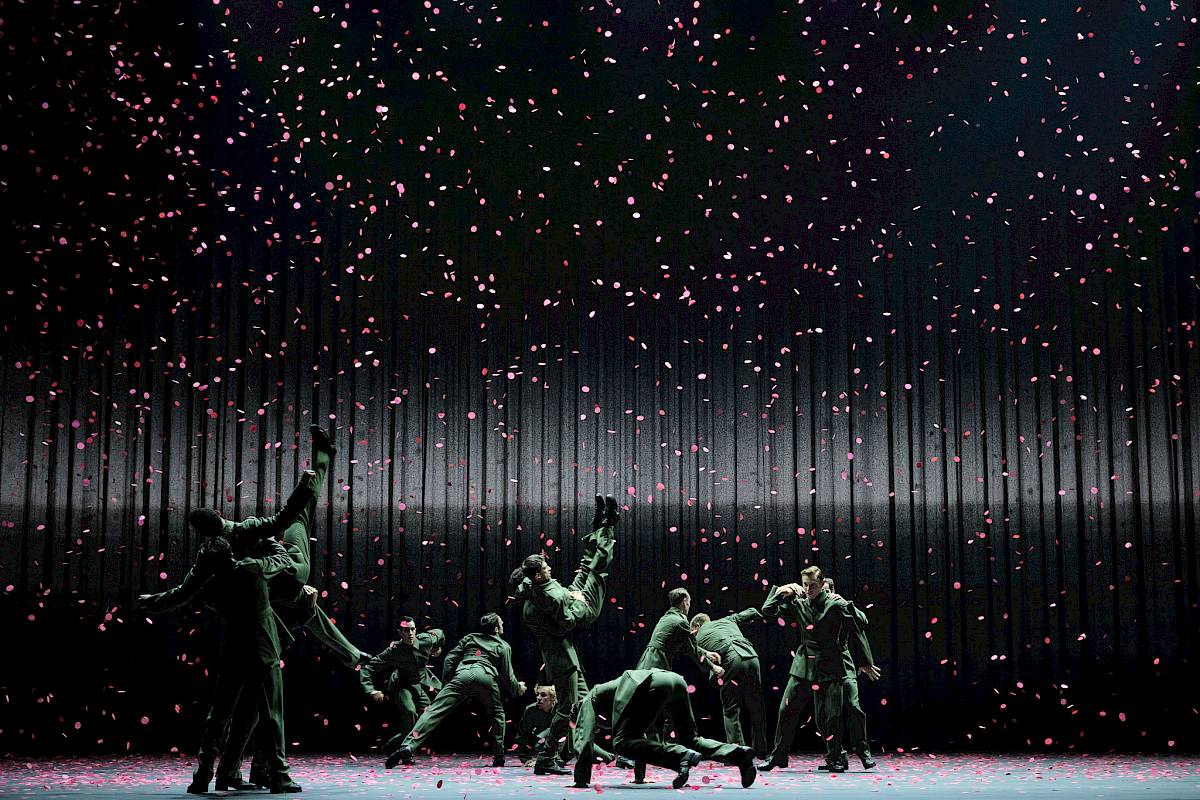

It’s a rare situation to hear a story in sound that you haven’t yet read. I only know the outline of what Ian McEwan’s 2001 novel Atonement is about as I sit in the rehearsal hall at Kreuzplatz and listen to the Philharmonia Zürich. Jonathan Lo steers the musicians through the second part of the ballet, which is based on the book, for the first time, and the score sounds so clear that images come to mind as if by magic – not only when military drums suggest the soldiers of the British army being evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940. Condensations, relaxations, large-scale rhythmic patterns, changes of register, impenetrable clusters, idyllic lines…

You can hear that it’s about conflicts, encounters and love. And that, last but not least, it is a film composer who is reading along in her large score a few metres behind the conductor and keeps looking happily into the orchestra. Laura Rossi travelled from London to Zurich for two days to clarify details with Jonathan Lo and Cathy Marston, the choreographer who conceived this project and expressly wanted Laura Rossi to be the composer. “What brought her to me was Battle of the Somme,” says Laura when we sit down together after the rehearsal. In a dazzling mood and speaking at breakneck speed, with “footage, 74 minutes” she summarises very succinctly what her special cinema hit is all about.

In the UK, practically everyone knows the silent documentary film about one of the most horrific battles of the First World War, which two British cameramen were sent to the Somme in the north of France to film in June 1916. Over a hundred French and British divisions and fifty German divisions faced each other. On the very first day, more than 19,000 British soldiers lost their lives, including many volunteers. Laura has a family connection to these bloody events, as her great-granduncle Fred was very lucky to have survived them. “As a 20-year-old stretcher-bearer, he belonged to the 29th Division, which also appears in the film, and kept a war diary. He died when I was ten years old.”

Although the silent film, shot before the battle and in its first nine days, also features shells and dead bodies – alongside cheerfully waving young men marching to the front in the summer sun – it was allowed to be shown in the UK in the same year and from then on held the record at the box office until Star Wars overtook it in 1977. In 2016, one hundred years after the battle, Laura Rossi was commissioned to write a new score for the film to be performed live in front of the screen, which a hundred orchestras, both professional and amateur, did with great success. As a result, Cathy Marston was struck by the special sensitivity with which the music was composed.

“Atonement is my first ballet score, and I really want to write another one,” says Laura, who is reluctant to be pinned down to the silent films, movies and TV series she works for. Just as important to her is what she calls “concert music”, autonomous music. In a way, writing for ballet is a path between the two and “definitely more difficult than a film score because the music carries everything.” How did she approach it? “I read McEwan’s book a few times to get deeper into it, and then there were a lot of Zoom meetings with Cathy, she in Zurich, me in London. With her, Briony, the main character, is not a writer as an adult, she is a choreographer, but the characters remain the same.”

As a thirteen-year-old in 1935, Briony was the first on the scene when her cousin was raped and, against her better judgement, she accused the Robbie that her older sister Cecilia loves. He is released from prison after enlisting as a soldier – whether he survives remains to be seen. “I have to get to the emotions before I write the music, and for that I also make drawings, in pencil, even for concert music, and then I go to the piano the old-fashioned way with music paper.” Are there certain patterns that she then falls back on? “No. I always try to be free, to be inspired only by the story and the characters. With every project, you start from scratch. I have experiments that I wouldn’t show anyone.” She laughs. She sent drafts of various scenes, converted into digital orchestral sounds, to Cathy Marston, and the discussions gradually resulted in what the Philharmonia Zurich now plays. The roles are also assigned solo instruments – the piano for Briony, the violin for Cecilia and the cello for Robbie. Laura masters two of these instruments herself, piano and violin, plus bass guitar.

That’s how she got into music in the first place – apart from the fact that her Italian father was a professional pianist and her English mother was an amateur singer on stage. Born in Birmingham and raised in the county of Devon, Laura played bass and piano in a big band at school, for which she also composed, and gained experience as a violinist in a youth orchestra. It was therefore an obvious choice to study a mixture of pop, jazz and classical music at the University of Liverpool. Because the course didn’t materialise, she went all-in on classical music, including composition and orchestration, and licked blood when it came to film music. At the London College of Music, she studied the subject up to a Master’s degree; with Shakespeare, Laura got into the practice: She wrote music for piano, guitar and string quartet for seven early silent films based on his plays, Silent Shakespeare.

You can also hear Debussy in it, one of the composers from whom she learnt a great deal about orchestration: Bernstein and Stravinsky, but also jazz arrangers such as Count Basie and Nelson Riddle. And she admires Ennio Morricone. “He has a unique ability to bring all the emotions of a scene together directly in his music, so the music can even stand on its own.” Are there standards that film composers have to adhere to today? “No, it’s a great time to be a film composer, there’s no one trend. There are big orchestral scores, experimental chamber scores, electronic scores, pop and jazz…”

Of course, it happens that TV directors set tight guidelines. But for the police series Redemption on ITV, the composer was even free to use a song written by her now 16-year-old daughter Marcella. Currently Laura is working on a piece for a huge children’s choir – 1000 voices! – and two orchestras in the London borough of Ealing, where she lives with her family. Children’s author Michael Rosen has written the text and the work will soon be premiered at the Royal Albert Hall. And the First World War is still on her mind: after the music for Battle of the Somme and another for the 1917 silent film about the Battle of the Ancre, it is now the turn of the Battle of Arras, another commission from the Imperial War Museum in London.

In Atonement, the war only occasionally characterises the events. Primarily the private drama got close to her heart while composing. What begins with an innocent summer’s day, “very simple piano music”, soon leads “to the darkest parts, to the rape scene”, and at the end of both the book and the ballet, Briony is an old woman with dementia whose memories become confused – “like my grandmother”, says Laura. The complex sounds she found for this shall not be revealed here. Only the composer’s maxim: “I want to help the audience understand what is happening.”